Following a visit to San Pedro Sula, Honduras, researchers from WOLA and the Women’s Refugee Commission traveled to Guatemala City, the capital of Central America’s largest nation, to speak with officials, scholars, and service providers about what migrants are experiencing in United States government custody. Here is what they found.

1. There has been a shift in who is being deported: from recent border crossers in 2024, to people who have lived in the US for years or decades in 2025.

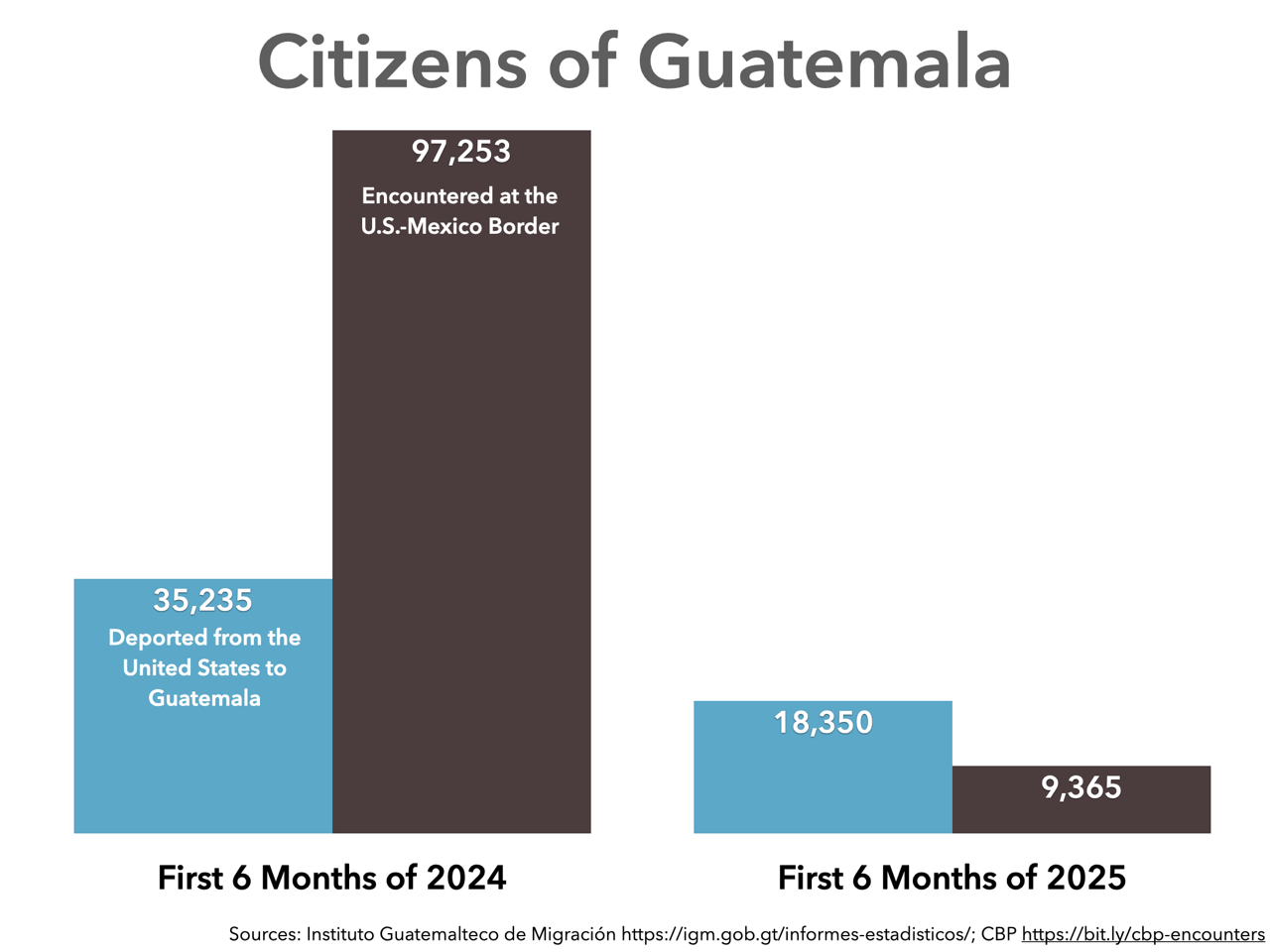

The airport here receives more US deportation flights than any other: 212 in the first half of 2025, according to Witness at the Border. During the first half of 2025, 18,350 citizens of Guatemala arrived aboard those flights. This represents a reduction of about 48% from the 35,235 Guatemalan citizens aboard 295 flights at the same time in 2024.

But the reduction is deceptive. The Guatemalan people removed from the US in 2024 were largely recent border crossers—people who had spent little to no time in the country. The population being returned in 2025 is very different. Those working with the deported population unanimously agreed that a majority are individuals who have spent a significant amount of time—years, or even decades—building lives and families in the US. As we found in Honduras, many of these deported migrants were forced to leave not only their lives but also their families, including children, behind. The emotional and mental health toll is severe.

The fact that more people have been deported to Guatemala than encountered at the border this year suggests that most of this year’s deportations were of people detained in the US interior, probably after living in the country for some time. With the early July passage of a giant funding bill for “mass deportation,” the blue column in the graph above is likely to grow sharply.

They are entering US custody through ICE operations in cities throughout the US, far more often than through Border Patrol or CBP actions at the border. Many are older and often have US citizen children.

A giant funding bill passed in early July (known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act) adds unprecedented resources to the Trump administration’s deportation machine—$45 billion for detention, $15 billion for deportation, and $13 billion to expand the size of ICE. These numbers are staggering: The budget for immigration detention is now more than 62% larger than the budget for the entire Federal Bureau of Prisons. With the vast scope and scale of these resources, the number of people removed after long periods in the US is very certain to grow.

2. Migrants are experiencing harm and abuse when arrested, in detention, and during deportation.

As with our findings in Honduras, our time in Guatemala reveals that this immigration enforcement is being undertaken dangerously, with migrants subject to needless harm and abuse. We asked service providers, government officials, advocates, and academic experts what they had heard from deported people about how ICE, CBP, and their contractors have treated them upon arrest, in custody, and during deportation. Once again, what we heard left us deeply concerned.

- Migrants reported to authorities and organizations incidents of verbal abuse, intimidation, and discriminatory language by guards in US detention facilities; some also described cases of physical mistreatment.

- One interviewee said they had documented two cases of gender-based sexual violence in ICE detention centers. One victim was an Indigenous woman who did not speak Spanish. The effective closure of the government’s own internal oversight agencies, the Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL) and Immigration Detention Ombudsman (OIDO), which monitor sexual assault and abuse in detention, suggests that these cases are likely going underreported.

- As in Honduras, we heard of denial of care to children, particularly during the often lengthy deportation process. “Children arrive with very dirty diapers because the parents aren’t able to change them,” a government official said. “They arrive unbathed, and, after spending many hours without eating, often dehydrated.”

- A government official confirmed that cases involving individuals with psychiatric conditions appear to be increasing this year. However, they noted that deportees are returned with psychiatric medications but no medical diagnoses.

- Consular officials are having greater difficulty accessing Guatemalan citizens in some detention facilities. An interview subject specifically cited the family detention centers in Texas as problematic in this regard.

3. Family separation is pervasive.

Echoing what we documented in Honduras, families with US citizen children are being separated, in some cases with little or no opportunity for parents to decide whether to bring the children with them. “People have to make instant decisions at what is the worst moment [arrest]. Under intense emotional circumstances, some are able to choose to be deported with their children or leave them behind, but others—probably the majority—are not,” a service provider told us.

As we noted in our Honduras dispatch, the scale of these family separations is likely to increase under the new Detained Parents Directive, which substantially reduces ICE’s existing obligations to facilitate reunification of parents with their children before deportation.

There seems to be some variability in the likelihood of family separation across ICE deportation staging areas. Two interviewees separately told us that people who departed the ICE facility in Alexandria, Louisiana, were more likely to report separation from their children than those flown from other sites like Harlingen, Texas.

4. Non-return of money, valuables, and identity cards is common.

Non-return of money, valuables, and identity cards is a common problem, though these initial conversations indicate that it might be less pervasive than in Honduras. In some cases, migrants told organizations that the cash they were carrying at the time of arrest was not returned after deportation. In others, officials told of migrants’ surrendered cash being replaced with stored value cards that, for some reason, “only function in the state of Kansas.” Identity documents often get returned to Guatemala “in a big load all at once,” days or weeks after their owners have departed reception sites, a government official noted.

5. Guatemala is providing reception services, but there are gaps.

Guatemala’s government is implementing a new “Return Home Plan” that offers some services to those arriving, with an option to take a 75-question survey about their backgrounds and needs while at a new reception center in the capital. Those questions, however, do not include any content about mistreatment suffered in the US.

What is needed, an official said, is “more time; you need a direct relation.” Some interviewees called for an ability to let people know that there is some entity with which they can talk, when they are ready, about what they experienced.

“The response isn’t in the airports, it’s at the local level,” said a longtime migration scholar who cited a rich “ecosystem” of social organizations, churches, local governments, and support networks in communities throughout the country where deported people are returning. However, many of these vital services are experiencing severe funding cuts, due the loss of USAID funding and other US assistance. The loss of these funds imperils our ability to document the abuses committed while in US custody, as well as migrants’ ability to rebuild their lives after deportation.

The testimony of migrants arriving following deportation is a crucial vector for learning about abuse, mistreatment, and potentially unlawful practices committed against them by US agents and contractors inside the US. As the deportation machine’s tempo increases, there is a critical need to gather information about the everyday abuses and the egregious cases, to document and verify them, and to ensure proper follow-up.

However, obtaining this information does not mean asking exhausted, highly stressed people about mistreatment while they endure the trauma of arrival at airports or reception centers. “Unlike last year, people are arriving in far worse condition—many don’t even want to talk,” a service provider recalled.

Next Stop: Southern Mexico

As we transit to Mexico, WOLA and WRC will continue to determine how to improve documentation and accountability, to ensure that examples of abuse, mistreatment, and unprofessional behavior do not go ignored, forgotten, or unaccounted for. We will not allow immigration detention to remain a black box.