As the United States’ immigration detention system becomes a black box, researchers from WOLA and the Women’s Refugee Commission are traveling through Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico to better understand the conditions faced by individuals recently deported from US detention centers—and how those conditions, particularly for women and children, have changed compared to previous years. After interviewing officials, service providers, experts, rights advocates, and deported individuals in San Pedro Sula, Honduras and Guatemala City, Guatemala, the team proceeded to Tapachula, a city in southern Mexico near the border with Guatemala.

In Mexico, we learned that human rights defenders and service providers in this region, battered by the US government’s budget cuts, have difficulty interacting with what, for now, is still a relatively small number of deported people, nearly all of whom leave Tapachula as quickly as possible.

Before they depart, Mexican authorities sharply limit access to them, complicating receipt of testimonies. The city’s poor security climate adds to the difficulty. For these reasons, our interviews in Tapachula yielded less information about allegations of harm done to migrants in US custody whom the US government has deported than our other site visits. Still, we obtained some important information and noticed disturbing trends.

1. Southern Mexico is a growing destination for deportation flights from the US.

A city of 350,000 in Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest state, Tapachula sits along a major route for US-bound migrants entering Mexico through its southern border. Since January 2025, though, the unlawful White House executive order banning access to asylum or other protection at the US border, along with knowledge of the climate of fear that the Trump administration’s policies have created in the US interior, has sharply reduced the number of people arriving from Guatemala.

Between February and May 2024, Mexican authorities reported encountering 165,001 migrants in Chiapas. During those same months in 2025, that number fell by 93 percent, to 11,620.

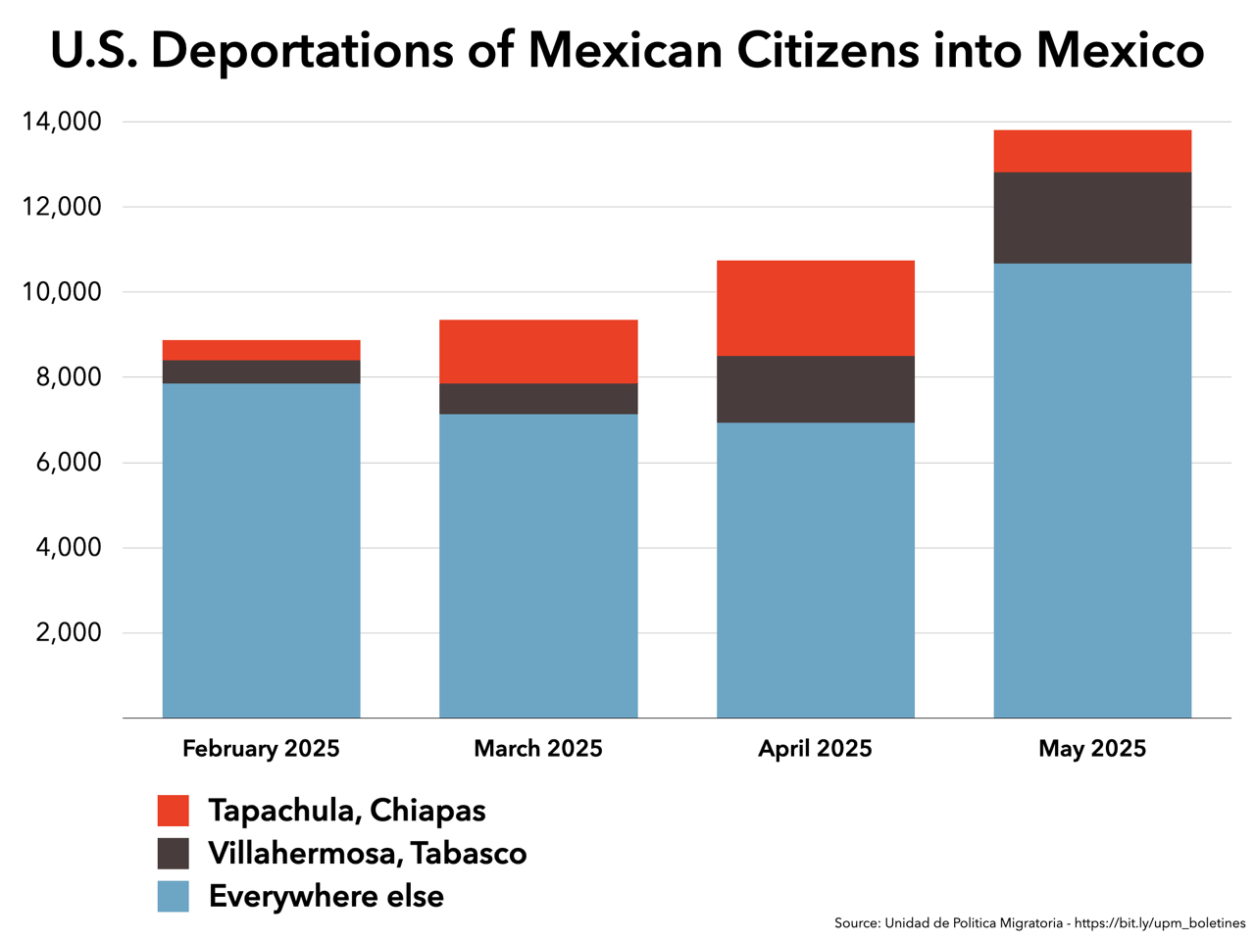

Instead, like San Pedro Sula and Guatemala City, Tapachula is now a growing destination for US deportation planes. With the pretext of sending them as far from the US border as possible, purportedly to ensure safer returns, the Trump administration began flying removed Mexican citizens here in February 2025 through the Interior Repatriation Programme (PRIM). Deportees are not given any choice of their destination within Mexico. Some service providers who managed to speak with returnees told us the individuals didn’t even know where they were being sent. This, combined with the fact that some were flown to southern Mexico, only to then be bused by the government back to Mexico City, raises serious questions about the logic and transparency of the process.

Since then—as of July 28, 2025—6,045 people had arrived in the city aboard 56 ICE contractor planes. The administration has sent a similar number to Villahermosa, the capital of Tabasco, another state that borders Guatemala. With the passage of the so-called “Big Beautiful Bill” in early July, which adds $14.4 billion to ICE’s aerial deportation budget through 2029, the number of flights to Tapachula and Villahermosa is very likely to grow.

So far, most of the Mexican citizens returned to Tapachula have been adult men deported alone, though some cases of family groups have also been reported. They come from all over the country; some are from northern states, flown to a city that is 1,000 or more miles from their homes, which are closer to the US border. “One guy was even from Matamoros,” a human rights defender told us. Matamoros is directly across from Brownsville, Texas, on the Gulf of Mexico, and it is almost as far away from Tapachula as one could be while still in Mexico.

“People arrive in shock,” this individual said. They are shackled by the hands and waist during the flights and often arrive not knowing where they are. “Mental health needs are great among the migrant population,” an international organization official said, referring to both the northbound and deported populations, “but nobody is really able to respond.”

2. Access to deported migrants is difficult.

Mexican migrants aboard the US planes, most of them captured after long periods of living inside the US, “arrive without having received any information while in detention centers, nor any guidance on what to do once in Mexico,” a Tapachula-based human rights defender told us. “They are very distrustful of anyone who gets close to them. They are very concerned about what they’ve left behind in the United States.”

Still, it is difficult to determine the extent of mistreatment and abuse that deported people are suffering in US custody prior to arrival in Tapachula, because opportunities for monitors to interact with them are scarce. Almost none of the people deported to the city stay there for very long, and for much of the time they are there, Mexico’s migration agency (National Migration Institute, or INM) is processing and transporting them at sites, and aboard vehicles, where aid agencies and monitors may not interact with them—presumably by design.

The INM, which faces frequent allegations of human rights abuse and corruption among its ranks, does not coordinate, or even have much contact, with human rights groups, aid groups, or international organizations in Tapachula. Getting a meeting is difficult: WOLA and WRC were turned down, and three different organizations in the city told us that INM had responded negatively to recent attempts to meet with officials. INM and the Mexican government’s refugee agency (Mexican Refugee Aid Commission, or COMAR) “have a very hostile posture toward organizations that denounce abuse, or that are parts of networks that denounce abuse,” said a non-governmental expert who has worked with migrants in Tapachula for years.

Most deported people accept the Mexican government’s offer of a 2,000-peso ($110) subsidy for bus fare. After a quick ride to Tapachula’s terminal, they depart for elsewhere in Mexico. While the Tapachula terminal may offer monitors a fleeting chance to inform people of opportunities to detail abuse or mistreatment, other deported individuals don’t even stop here. Since July 15, INM has been transporting some people who come from northern Mexico all the way to Mexico City’s Terminal del Norte bus station. They don’t see Tapachula at all.

When deported migrants arrive in Tapachula, then, they spend most of their time in the custody of agencies that keep outside monitors, service providers, and advocates at a distance. “There’s no entry into the reception area; we have to stay in the common area of the airport,” a human rights defender said. “We can only talk to any migrants left over” who remain briefly at the airport before departing. This makes it much harder to learn about what repatriated individuals experienced in US custody.

Tapachula’s municipal government had considered setting up shelters to prepare for deportations, and officially, the Mexican government says it is relocating its repatriation centers—moving the one in Nuevo Laredo (along the border with Texas) to Tapachula to improve deported individuals’ access to services. As of now, no such center exists, and the municipal government has not received any deported people.

Mexican citizens are not the only US deportees in the city. On July 11, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum told reporters that the US government had deported 6,525 citizens of third countries to Mexico since the Trump administration began. It appears that these non-Mexican citizens are not being flown to Tapachula (at least not yet).

However, these third-country citizens still end up in Tapachula and elsewhere in Mexico’s far south. When US authorities send them into a northern Mexican border city, the INM quickly places them on buses that whisk them across the country to Tapachula or Villahermosa. (The agency delivers some citizens of Central American countries directly to the Guatemalan borderline, too, with the expectation that they will keep going south.) No source had any clear sense of how many non-Mexican citizens have been bused to Tapachula this year, much less how they could be contacted to discuss their experience in US custody.

As we were not able to learn as much in Tapachula about abuse that migrants have suffered in US custody, much discussion centered on potential strategies for hearing complaints and testimonies once, as is very likely, deportation flights to the city increase. Tapachula will need a reception center to link people with services, as well as, perhaps, a “module” or other semi-constant presence in the city’s bus terminal. Such spaces should offer opportunities for people to share their testimonies of involuntary family separation, non-return of valuables, misuse of force, neglect that endangers health (including the health of pregnant and lactating mothers and their children), and other cruel treatment.

3. Deportees face rising insecurity.

Deportees will need support in a city that has grown sharply more dangerous in the post-pandemic period. The state of Chiapas—a longtime corridor for cocaine transshipment, migrant smuggling, and human trafficking—has seen an upsurge in criminal violence between trafficking groups competing over territory. In October 2024, an urban public security poll taken by the Mexican government’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) found Tapachula to be the Mexican municipality with the highest proportion of residents (91.9 percent) judging it “insecure.”

Now, with fewer northbound migrants, the city is in a sharp economic downturn. Landlords, cab drivers, grocers, restaurants, and other service providers have fewer customers. Among those losing income are criminal organizations that were smuggling migrants, and those that were preying on them, often kidnapping them for ransom—a “business” whose victims suffered assault, sexual violence, and torture. Kidnapping became so widespread—with the apparent collusion or acquiescence of government officials—that by 2024, kidnappers were issuing paper bracelets or hand stamps that served as proof that their released victims had paid.

Women have been frequent victims of sexual violence associated with ransom kidnappings in the Tapachula area. One international organization’s staff indicated that women from Haiti have been especially vulnerable: Language barriers make it difficult for survivors to report these crimes or begin asylum procedures. If the number of deported women and girls increases, there is real concern that similar patterns could become more widespread.

As these violent actors’ income streams have dried up, they are turning to Tapachula’s non-migrant population. Extortion of businesses, from restaurants to informal street vendors, has worsened across the city.

Tapachula’s security climate further complicates the situation for people aboard the deportation flights. If more planes arrive in the coming months, some people may be left stranded in the city due to insufficient resources and networks. Here, they will be vulnerable to kidnappers and extortionists. “The entire criminal infrastructure that thrived on northbound migration will very likely shift its focus to deportees,” warned a human rights defender.

The danger extends to human rights defenders and humanitarian workers who assist migrants in the city. One prominent local group’s members rarely make the 20-mile trip from Tapachula to the Guatemalan border anymore because their work to reveal kidnappers’ activities and state collusion brought a wave of threats. Government-issued security measures, like GPS-enabled “panic buttons,” offer little reassurance of protection. “This is our problem,” a staff member from that group said, “but what about the people we serve who are always on the street?”

4. The US aid cuts have already drastically reduced support for migrants—and they leave the region unprepared for a surge in US deportations.

Tapachula’s human rights monitors and humanitarian workers have been another group hit by the US government’s severe 2025 cuts in aid for programs seeking to guarantee migrants’ safety and ability to integrate into Mexico. Because of the funding cuts, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has reduced staffing in southern Mexico, closing offices in some cities and downgrading others from offices to “field presences.” Service providers that received support, either directly from the US government or from UNHCR and other international agencies, are closing doors, laying off staff, and canceling programs. Gender-based violence-related services, as documented elsewhere in the region, have been among the most heavily affected.

The Trump administration is sending people to an environment that is ill-equipped to receive them. A city with a long experience of migration but no experience of receiving US deportees, Tapachula may one day become an important site for monitors to learn about the treatment that Mexican citizens are receiving in US custody before and during deportation. For now, the necessary infrastructure and relationships that would allow this are far from being in place.