To support and uplift local experience and expertise, WRC partners with local researchers to produce our groundbreaking reports. These researchers often have deeply personal connections to, and unique takeaways from, the work. In this new series, we give them the floor to share their reflections.

First up is Diana Flórez. Diana is originally from Colombia and currently lives in San José, Costa Rica. Diana researched our recent report on the impact of US humanitarian aid cuts on women and girls in Honduras.

Here’s what Diana had to say:

I feel a very personal connection to WRC’s work. What moves me most is that WRC chooses to work in places that are often forgotten, where the stories of displaced, migrant, and refugee women are rarely seen or heard. WRC looks beyond the headlines to places where violence may not make international news but where its impact on women’s and girls’ lives is devastating. Honduras is one of these places, and WRC has chosen to make it a priority—a country seldom mentioned in global policy debates yet marked by deep and complex forms of violence that shape everyday life, and where support systems remain fragile.

But my strongest connection to WRC comes from the women the organization works for—those who were forced to flee their homes and are now being deported back to the same dangers they once escaped. These women are not, as some have unfairly called them, “the worst of the worst,” but women who had to make a “choiceless choice”: to leave in order to survive.

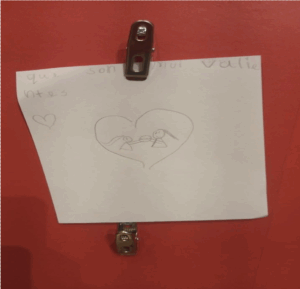

My six year-old daughter already understands this in her own way. At an exhibition about women on the move, she was asked to write what she thought about migrant women. Her note said simply, “They are brave.” That moment stayed with me. It reminded me that even a child can recognize the strength and dignity of migrant women—women whose humanity is so often stripped away until their suffering becomes invisible. Seeing how naturally my daughter understood what part of society still fails to see made me realize why the work WRC does, and that I am part of, matters so deeply.

When WRC and WOLA invited me to contribute to a new report that will help shed light on the treatment of my compatriots in US detention centers, my immediate answer was yes. We need to confront the dehumanization of migrants, which, as the Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman explains, paves the way for their exclusion from the very category of human rights holders and strips their suffering of its moral weight. Once a group is seen as “undeserving” of empathy, almost any form of abuse can be justified or ignored—as Bauman also reminds us. And this is exactly what we are witnessing in the United States today.

One of the ways to resist and challenge this dehumanization is by documenting, naming, and restoring the moral and human significance of these stories. My commitment became even stronger when a young man who had just been deported told me, “They treated us worse than animals. They chained our hands behind our backs and threw the food on the floor so that we had to pick it up in a crowded cell.” How can we allow this to happen?

There were many things that really surprised me [while doing research for the new report], but what stayed with me the most were the stories of how migrant women are treated in US detention centers. You can clearly see how gender-based violence overlaps with institutional, physical, and psychological abuse. When we spoke with service providers in Central America who receive deported migrants and asked how pregnant women were treated while in detention, the answer was always the same, “There’s no difference—they’re migrants.” That’s the only category that seems to matter.

And children fall into this same category. They’re often treated like adults—as if they have to pay for migrating, or simply for being born to migrant parents. Service providers told us that children in detention often lack proper food and safe places to sleep, and that no one takes the time to explain what’s happening to them. Imagine being a child and hearing that you’re being sent to a country you’ve never known, after already going through so much. Psychologists told us that when these children draw, their pain is visible—they draw prisons, handcuffs, angry faces.

A moment that really stayed with me was an informal conversation I had with a trans woman who had just been deported and was waiting to speak with the psychologist at a reception center for returnees. She told me that what she went through in the US detention center was, in her words, “a nightmare I want to forget.” The first thing they told her when she arrived was that there were only men and women—and that they put her with the men. The guards made obscene comments and forced her to undress in front of others. After that, the touching and harassment became part of her daily life. She told me she actually felt relieved to be deported and to leave the detention center—even though the same threats and dangers that had forced her to flee were still waiting for her back home.

What happens in the US resonates globally, reinforcing exclusionary ideas that normalize violence and neglect towards migrants. The consequences are profound: When states and societies internalize this narrative, protection for migrants becomes even weaker. It’s no longer just about responding to US policy; it’s about how that policy reshapes local attitudes and institutions everywhere. That’s why it’s crucial to strengthen alliances among those who resist these narratives and continue defending migrants’ rights—even when doing so is politically inconvenient.

One of the questions we heard most often, both from deported people and from service providers, was, “And now what?” We know these abuses are happening, but how do we respond to them from Honduras, from Guatemala, from Mexico? The responsibility of our countries to receive and protect these people must be a priority. Honduras, despite being one of the poorest countries in the region, is providing care and welcoming its citizens back with dignity. The people working in the migrant reception centers are extraordinary. With very little, they manage to make returnees feel at least a sense of warmth when they set foot on home soil.

But we can’t stop there. That assistance is emergency and short-term. We need to think about what happens next. If someone is deported and separated from their family, how do we help them reunite? If a woman is returned to a community where she faces a high risk of being killed, how do we protect her? How do we provide legal advice, psychological support, and real safety? These are the questions that must guide our efforts now. This is where our focus needs to be—on building responses that restore dignity and protection for those who have already suffered too much.