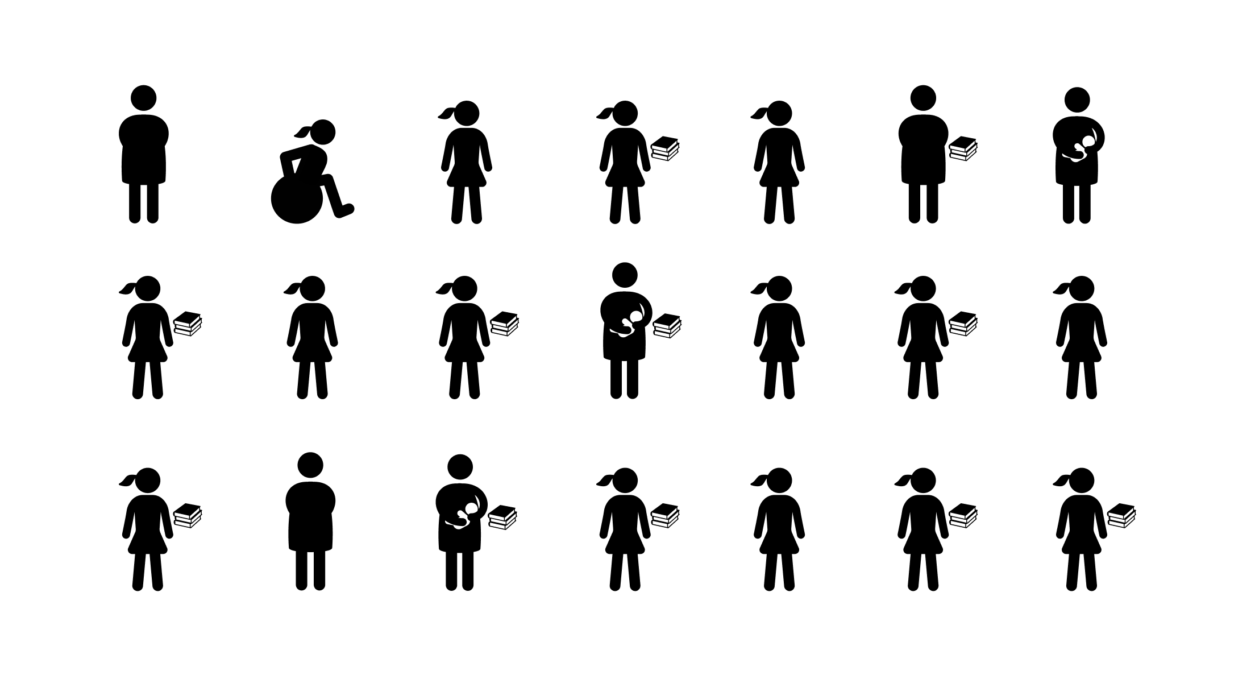

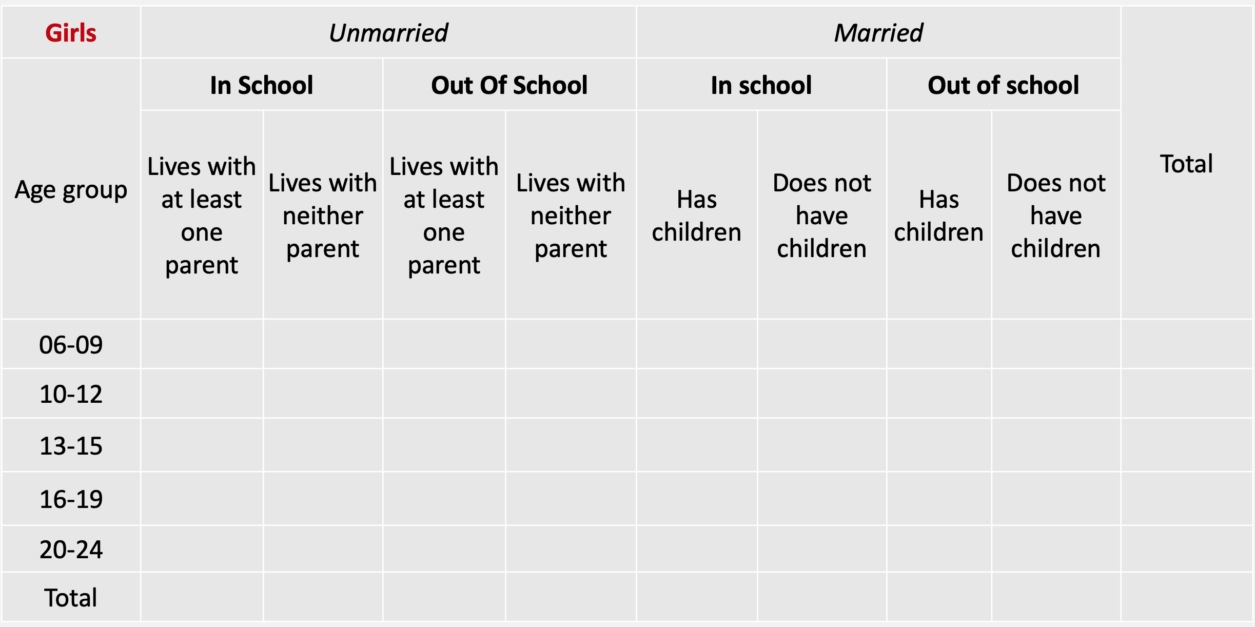

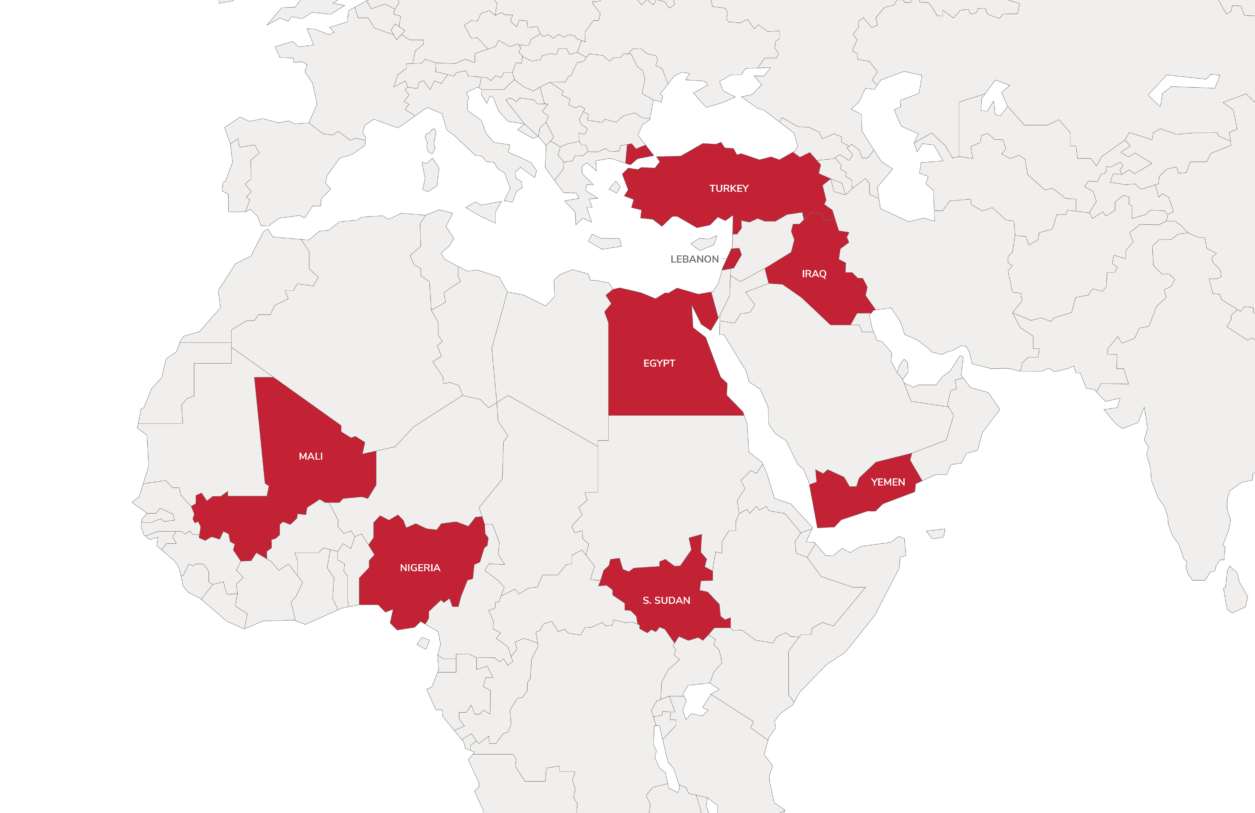

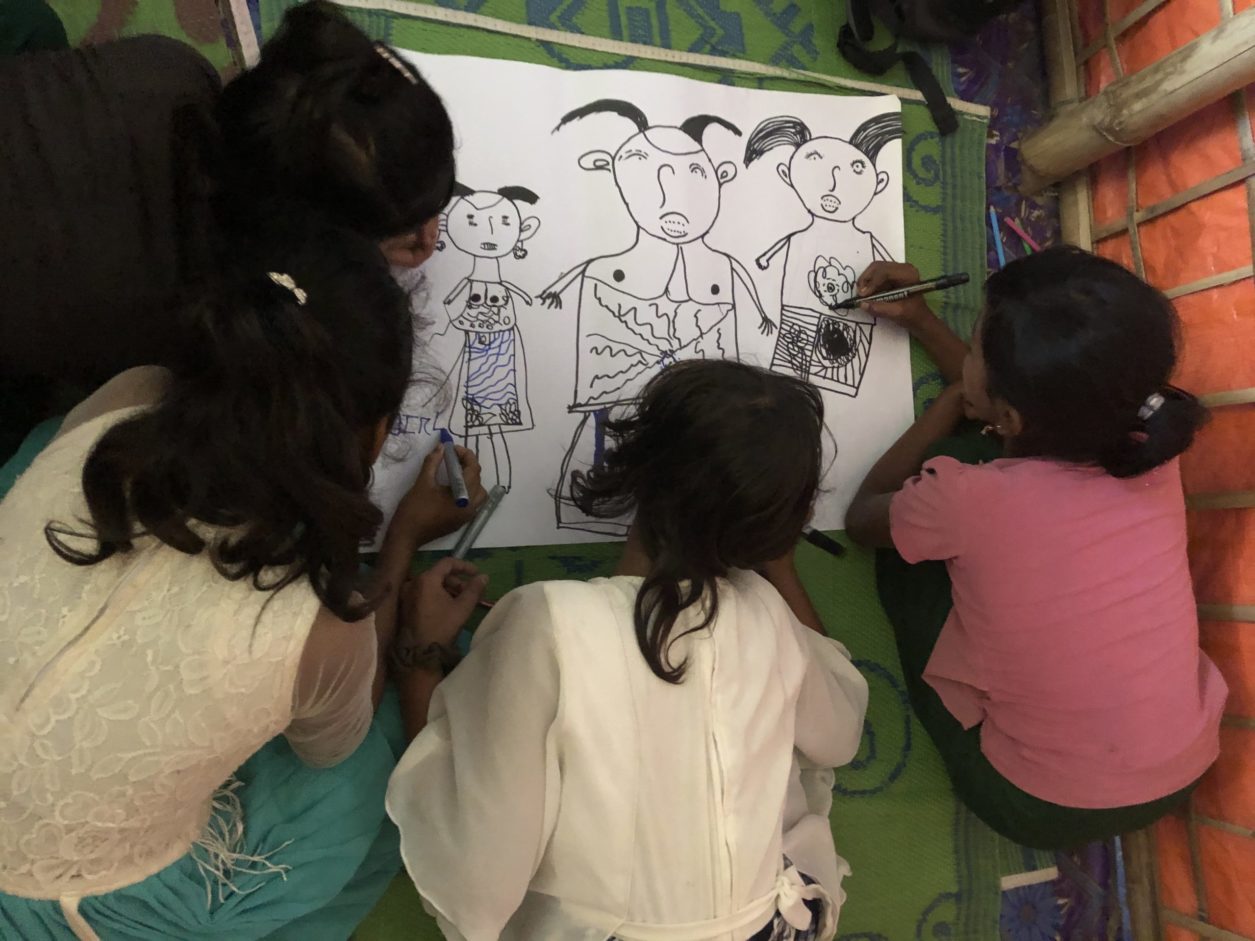

I’m Here is an operational approach that helps implementing partners reach the most vulnerable adolescents and supports partners in being accountable to adolescents’ safety, health, and well-being.

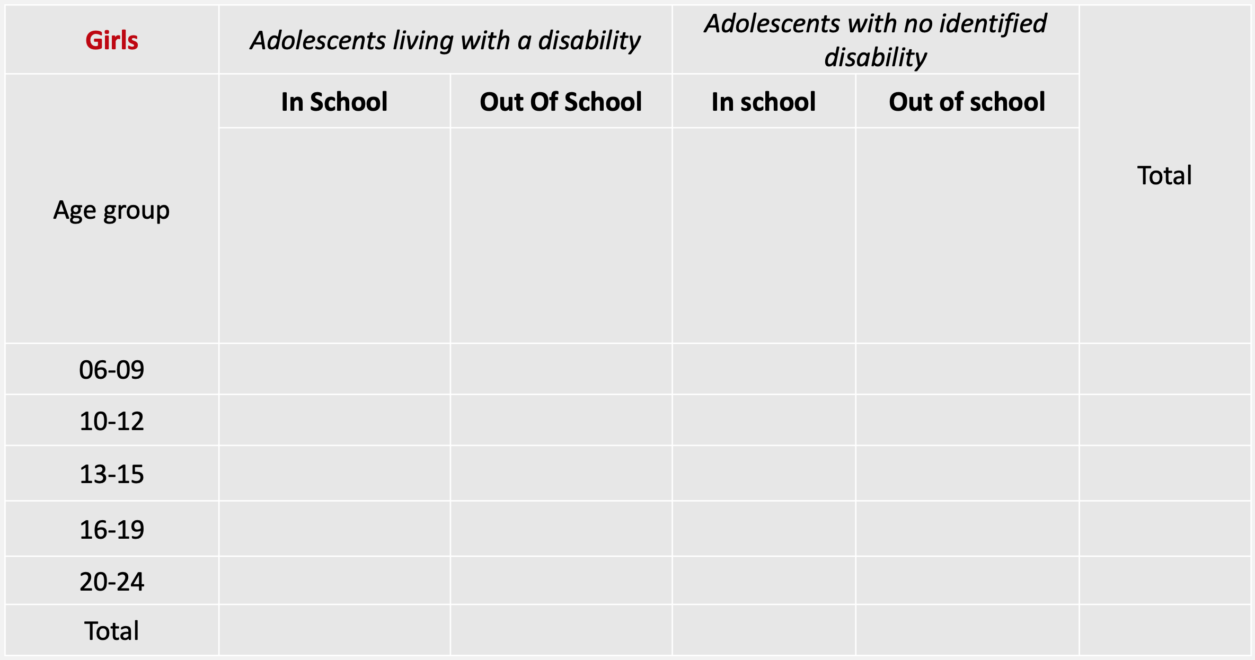

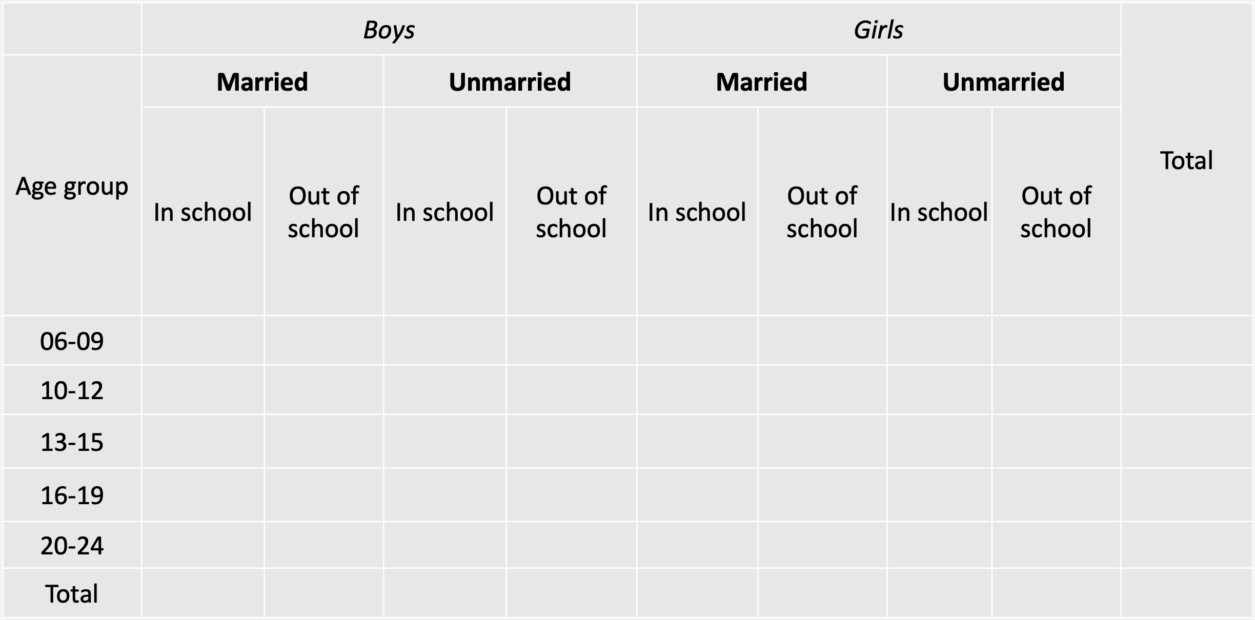

I’m Here enables humanitarian actors to engage adolescents in creating their own solutions—ensuring their rights are protected and programs are effective. The approach urges practitioners to go beyond seeing adolescents as a homogenous group, and to advocate for multisectoral action to meet the needs of different sub-groups of adolescents. I’m Here is adaptable to varying on-the-ground situations to ensure inclusion and engagement with adolescent girls and boys.

Younger

Younger Older

Older In-School

In-School Out-of-School

Out-of-School Married

Married